Namibia: African success story or elite propaganda

An earlier version of this article was initially published on JerichoOnline on the 30th of July 2018 I have updated it in light of the Namibian Fishrot scandal

On the 25th of July 2018, Samuel Shali Nghihepa, a sergeant in the Namibian Police Special Reserve Force Division, murdered his ex-girlfriend, Alina Kahehongo, in full view of her colleagues at a local supermarket in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital, before turning the gun on himself.

This was one of many cases of so-called “passion killings” which have rocked the nation in the past few years. Dozens of such cases occur every year, in which women (primarily) are murdered by their lovers. This appalling incident has once again left many Namibians asking “why?”, and has brought the Namibian police force under greater scrutiny.

In early July 2018, a 20-year-old man had murdered five of his family members. In both instances the police had received tip-offs, but took no action.A local radio DJ attributed this epidemic to mental illness. Whilst mental health is a real issue globally and Namibia is no exception, perhaps it is Namibia’s social fabric that we must scrutinise; Namibia is often portrayed to the outside world as a success story, in large part due to its impressive stability compared to other countries in the region. But even aside from these violent killings, Namibia still faces some extreme challenges, many of which are a legacy of its 20th century violent experiences.

The first genocide of the 20th century

Between 1904 and 1908 German soldiers committed the first genocide of the 20th century. Led by General Lothar von Trotha, the German forces set out to annihilate the Ovahereros and Namas in South Western Africa in a brutal war which involved poisoning water sources and the mass confiscation of property. The order given by the general in October 1904 did not mask his intention:

“Within German borders, every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will no longer accept women and children, I will drive them back to their people or I will let them be shot at.”

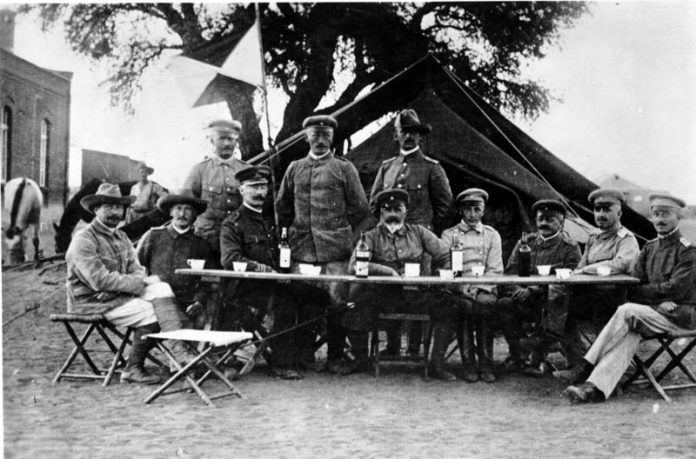

General Lothar von Trotha (centre, standing), Oberbefehlshaber (Supreme Commander) of the protection force in German South West Africa, Keetmanshoop, 1904. Photo credit: Bundesarchiv Bild/Wikipedia Commons

What followed from the General’s remarks was genocidal. However,hitherto August 2004, the German government had not officially apologised for the atrocities. Most importantly, for the first time the Germany government referred to the atrocities as ‘genocide’.For years Germany had been avoiding referring to what happened in Namibia as genocide. However,to this day there has not been any agreement on the form of compensation to be provided by Germany to the victims’ descendants.

After World War I, control of Namibia (then called South West Africa) passed to South Africa, which was given a mandate to administer the territory by the League of Nations until it was sufficiently prepared to act upon its own self-determination. South Africa interpreted this as an invitation to formally annex the territory and went on to rule it under a system of apartheid.

Apartheid and independence

South Africa held on to South West Africa for arguably three main reasons. Firstly, the vast mineral resources in the country were exploited for the benefit of white South Africans, and secondly Namibia provided a buffer from the guerrilla war which was raging in Angola between the Cuban-backed MPLA and the UNITA movement supported by South Africa Defence Force (SADF). The third reason was more of an international matter involving the United States and the British. The former saw South Africa as a bulwark against Communism and the latter badly needed South African and Namibian uranium for its nuclear weapons project. Thus, South Africa’s actions in Namibia were largely ignored.

Despite this,there was growing opposition to South African rule. Namibians began to agitate for independence. An insurgent movement, the South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO) was set up under the leadership of Sam Nujoma and began fighting what is commonly known as the South African Border War between 1966-90. With assistance from the USSR and China, the independence movement prevailed and Nujoma became the country’s first democratic president following the 1989 multi-party elections.Since then, the SWAPO party has held power. President Hifikepunye Pohamba took over from Nujoma in 2005, and handed over to the incumbent, Hage Geingob, in 2015.

Post-apartheid performance

Despite, or perhaps because of, SWAPO’s record in bringing about independence from South Africa, the party has been criticised for abusing, torturing and detaining members suspected of spying for South Africa during the liberation struggle. In 2000, an organisation called Breaking the Walls of Silence released a list of 700 people which it alleged to have disappeared during the liberation struggle whilst in the hands of SWAPO.

Despite progress made in addressing development challenges since independence in 1990, income inequality in Namibia remains one of the highest in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 0.56. #InequalityConf2018 @EANamibia @HSFNamibia pic.twitter.com/IGcZk6zk0m

— The Namibian (@TheNamibian) July 26, 2018

This matter has not been fully investigated and resolved but SWAPO seems to have applied similar heavy-handed brutality to its opponents.A case in point being how it dealt with the Caprivi conflict. After the Caprivi Liberation Army’s (CLA) ill fated secession attempt in 1999, in which a CLA raid on the strategically vital region of Caprivi was quickly crushed by the Namibian army, the government rounded up hundreds of suspects, many of whom were tortured and detained for prolonged periods without trial. Neither of these matters have been addressed satisfactorily by the SWAPO and could be contentious in the future.

A true success story?

Nevertheless, Namibia has been hailed as one of African success stories, especially since it inherited a highly unequal country at independence in 1990. The country’s efforts in reducing poverty have been largely recognised as successful, and in 2015 then-President Hifikepunye Pohamba received the Mo Ibrahim prize for African Leadership. In recent times, though seemingly reinventing the country’s name, US President Donald Trump praised Namibia for its efforts in self-sustaining its health care.That said, what these success stories often miss is the searing inequality of the country and its effect on socioeconomic development. Namibia remains one of the most unequal countries in the world. Windhoek in particular is notorious for egregious rental and property prices.

Windhoek’s development is deeply unequal. Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons.

In addition to this, Namibia has high levels of youth unemployment: according to the World Bank, Namibia’s youth unemployment was 44.9% in 2016, an increase from 39% in 2014. When the current President Hage Geingob came to power in 2015, he vowed to fight poverty in all its forms, establishing a Ministry of Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare.However, his term in office has coincided with an economic recession. In 2017 the economy shrank by 0.77%, and Geingob’s administration has reacted by implementing austerity. Latest statistics indicate that the country is now facing a recession having contracted for four consecutive quarters.

Much to be done

Despite enjoying a significant level of stability in relation to many countries in the region, Namibia still needs to do a great deal to foment social cohesion – but due regard must be given to the fact that in a nation of 2.5 million people with 13 ethnic groups and a dark colonial and apartheid history, this is no mean feat. Across major news outlets, few of these negative aspects are reported on. There is much coverage of the country’s positive profile. Some might argue that this is a good thing, given the generally dismal picture painted of Africa by media around the world. In my view, the answer for this lies in the country’s inequality: it suits the well off to present an affluent face to the world while burying and failing to acknowledge difficult truths. What is certain though is that Namibians need to address the legacies of post-colonialism and post-apartheid as soon as possible. Such a process woould involve reckoning with the past and the system it has installed to build a constructive future.

Postscript

I initially wrote this article as an alternative voice to a seemingly one-sided view to the economic, social and political situation in Namibia. My argument at the time was that we needed to avoid superficial views on the state of post-colonial nations. In many instances, stable nations like Namibia may appear as being successful. This often masks the conditions of the poor and vulnerable whilst simultaneously raising the profile of elites. Looking back, I think I have been vindicated following Al Jazeera’s publication of ‘Anatomy of a Bribe’. Al Jazeera’s work clearly points towards elites working in cahoots with foreigners to plunder the country’s resources at the expense of the majority.