South Africa must expropriate capital without compensation instead of land

I initially wrote this article sometime in April 2019. At the time, South Africa was gearing for elections. One of the most contentious issues during the run up to the election was land expropriation without compensation. Unsurprisingly, the matter illicited heated political debate. Against this background, on the 22nd of May 2019, President Cyril Ramaphosa came into power. Since then, the matter seems to have fizzled away because of other pressing matters. Notwithisting this, land expropriation debate must not be forgotten not least because demagogues might use it in future plebiscites . Therefore, I have decided to publish the article in almost its original state below:

Southern Africa has been making global headlines in recent times. In September 2018, there were reports that Zambia defaulted on a Chinese loan putting its national energy corporation at risk of takeover; whilst on the South-West, Namibia hosted a conference to discuss the emotive issue of land reform. Meanwhile in South Africa, following President Cyril Ramaphosa’s state visit to China, the Chinese President Xi Jinping’s had effusive praise of the country’s land reform programme. Not surprisingly, because of China’s inexorable economic influence in the region, Xi Jinoing’s ratification of South Africa’s land expropriation without compensation was significant.

However, as I argue in the following sections, the issue of land reform is of a secondary nature. Instead, what is of immense importance for social justice is the exproproation of capital without compensation. To put this into context, we need to go back to 1994.

A Negotiated Settlement

In 1994, democracy dawned in South Africa after a negotiated settlement. For almost 50 years, South Africa was goverened by a hybrid system encompassing elitist democracy and majority authoritarianism. Now, 25 years after the demise of apartheid, South Africa is grappling with high levels of unemployment and one of the highest levels of inequality. Most black South Africans, who are the majority, remain economically disadvantaged. Because of this, fissures have started to emerge in the country’s unsustainable political settlement. Thus, populism has started to thrive, and the new frontier is land expropriation without compensation. And yet, it remains unclear whose interests land expropriation without compensation is set to serve.

Chinese interests in land reform

Recently, Jacob Zuma, former South African President weighed in on the debate. Surprisingly, for 8 years as head of state he did not do much to address the problem.

My opinion on the land issue - 2 pic.twitter.com/S0zS3h07Dl

— Jacob G Zuma (@PresJGZuma) January 2, 2019

Perhaps, Jacob Zuma’s views explain why right-wing groups led by AfriForum are arguing that the proposed policy is aimed at advancing Chinese interests. During President Xi Jinping’s state visit in July 2018, the Chinese government committed to building a $10-billion metallurgical complex in a special economic zone in Musina-Makhado. Because of this, it was alleged by AfriForum that the expropriation of two Musina-Makhado Akkerland Boerdery farms was to exploit coal reserves on the land. The expropriation order was however challenged and repealed. Possibly this explains the dalliance of the Chinese leader to Pretoria’s land reform programme. Meanwhile, in December 2018, the 2019 Expropriation Bill was gazetted paving the way for a ‘radical’ land reform program. Nonetheless, the raucous debate seems to be a battle of white monopoly capital and an elite petty bourgeoisie.

A battle between white monopoly capital and the petty bourgeoisie

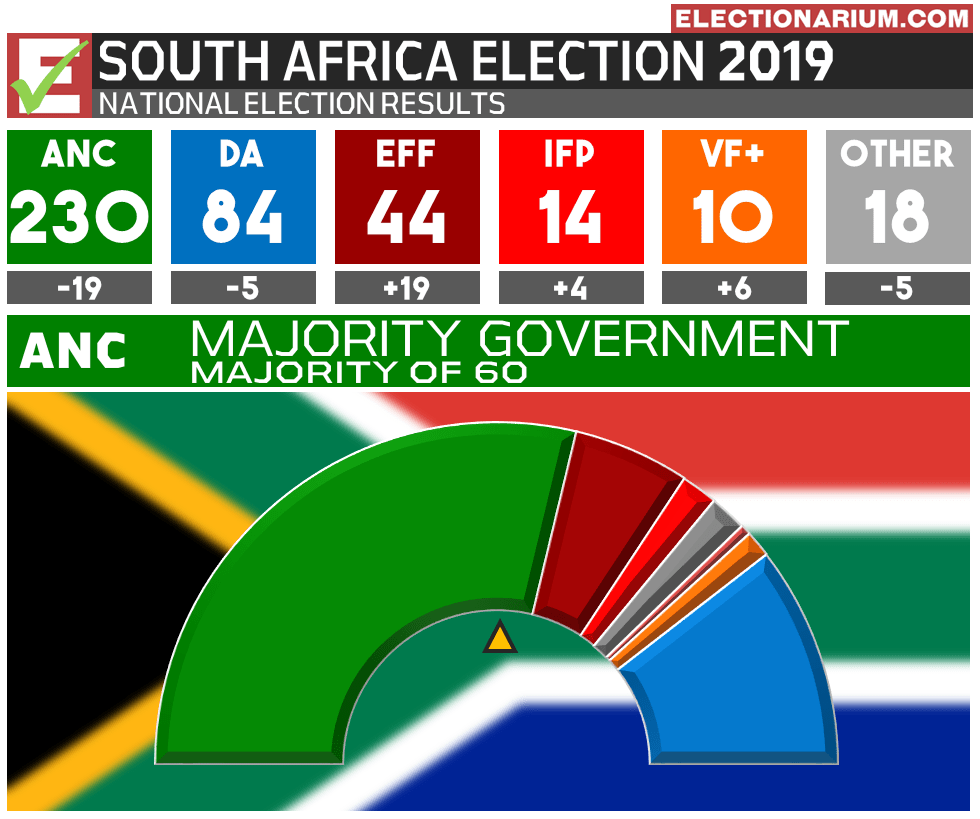

South Africa’s black ruling elite argue that the objective of land reform is to address past injustices. However, the insincerity of this assertion is almost shameful given the government’s failure to deal with the matter for the past 25 years. What is indisputable is that President Cyril Ramaphosa will not take a radical approach to land reform. For instance, in his manifesto speech land reform was given a cursory glance reflecting how unimportant it was. Yet, opposition parties such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and Black First Land First (BLF) latched on land reform rhetoric as a means of growing their share of the electorate. Consequently, the EFF emerged stronger after the election. The ambivalence of the ANC on land reform might have contrinuted to this outcome.

The EFF emerged strongest after the 2019 elections since its establishment

Meanwhile, the property owning mostly white groups intransigently argue that expropriation is a blatant disregard of property rights. Hence, battle lines seem to have been drawn between the various classes. The ANC has already indicated its willingness to ally with the Chinese on the matter-arguably to generate the much needed jobs. Given this, it seems the outcome will be a settlement between powerful groups in the country’s political economy. Undoubtedly, subaltern groups will take subordinate positions as happened in 1994. A key reason for this is because the current debate ignores how land is capitalised.

An alternative view

Contrary to Jacob Zuma’s assertion, the real issue in South Africa is not land reform. Rather, it is the failure of the ANC government to implement policies that would have evoked structural change in the economy. Dishing out land to cronies and elites will not end extreme poverty and inequality. Because of this, South Africans must assess the country’s capital structure to determine where and how wealth is being accumulated. A major reason for this is because in a capitalist economy land is only valuable to the extent that it can be financialised, and banks play a central role in this process. If this is not taken into account, South Africans might find themselves in a similar position to their Northern neighbors in Zimbabwe who are struggling to capitalise acquired land.

But most importantly, the fight against apartheid was not to gain the right to cast votes only. On the contrary, people sacrificed their lives because they wanted to participate meaningfully in the economy. Unfortunately, the alliance that emerged after the end of apartheid has failed to realise this dream. New coalitions with the Chinese amount to nothing but an enlargement of the bourgeoisie clique. Indeed, land was violently dispossessed but frontiers of accumulation have shifted from land towards finance. Accordingly, debate should be about capital expropriation without compensation.