Why private schools must be banned in Zimbabwe

Last month I was involved in a bitter debate on Twitter about private schools in Zimbabwe. The discussion was sparked by pictures which seemed to showcase fees paid by parents of children at privately run Riverton Academy. It turned out that parents forked out up to USD$6 200 in school fees for the term commencing January 2020. In a country facing severe economic challenges, I posited that this was so ridiculous as to warrant the banning of private schools. This train of thought elicited visceral reactions which inspired me to undertake some research into the matter. Fortunately, others before me have sought to confront the private school problem. Most notable is an article by Mako Muzenda a former private school student. Muzenda chronicled from her experiences how private schools promote Eurocentrism, whiteness and elitism. Therefore, after going through some literature, I have come to the conclusion that private schools have no social relevance except the perpetuation of past injustices. To contextualise this argument, one must go back to the history of education in Zimbabwer.

A brief history of education in Zimbabwe

No matter how you view it, education in Africa is a patently foreign concept having been brought to the continent by colonialists. The work of Mugomba and Nyaggah on the political economy of colonial education in Southern Africa is highly instructive. The authors rightly point out how the educational system in Africa was designed to promote capitalism and European values. In view of this, Mugomba and Nyaggah are absolutely right when they state that:

The colonial school system educated far too many fools and clowns, fascinated by ideas and way of life of the European capitalist class. Some reached a point of total estrangement from African conditions and the African way of life….

The roots of this outcome lie in the structure of African curriculum and instruction. During the early stages of the colonial era until World War II curriculum originated with mission schools. Missionary education was about converting Africans to Christianity. In the case of Zimbabwe, the interwar period was characterised by miniscule investment in African education relative to that of European settlers. After World War II, curriculum changed to meet the teaching method of the Phelps-Stokes Education Commission.The Phelps-Stokes Commission was founded in 1911 to ameliorate the living conditions of African Americans through better housing and education. However, as argued by Eric Yellin, its de-facto objective was to control how black people operated in white society. With this vision in mind, on the 25th of August 1920, the commission set out to study education in Africa. The outcome of the commission’s investigation marked a turning point in African pedagogy. Most significantly, the commission advocated manual labour as the preserve of most Africans. Thus, Africans were best suited to occupy worker positions with their managers being Europeans. Furthermore, vocational learning was considered the most appropriate form of learning.

Colonial conditions and the demand for education by black Zimbabweans

Between 1920 and 1945, there was a 271% increase in African students enrolled at mission schools (from 43 094 to 159 770). A key reason for this was the worsening conditions of the rural based black population. Land alienation and the resettlement of Africans into reserves had a negative effect on living conditions. Because of this, most Africans came to perceive education as a way out of poverty. Despite this, job opportunities for educated Africans were scant. Moreover, there was a misguided belief that education would give Africans a chance to compete with the minority settlers. Yet the educational system was designed in such a way as to maintain the power of the minority over the majority. Most significantly, education inculcated self-hate in the African. This is observable in contemporary times as one’s social standing is often related to perceptions of their education.

In summary, it has been shown from this review that African education as brought by colonisation did not instil critical analysis and thinking. In addition, we see that African education was designed to ensure the availability of cheap labour for colonial settlers. In contrast, European settlers invested large sums of money in exclusively white private schools. Unsurprisingly, private schools received and continue to receive superior education over missionary and government schools. As a result, the majority of Africans to this day do not have the opportunity to learn the skills and competencies which allow them to compete with the minority elites. The term elite is used here to refer to a class of people comprising of the ruling bureaucrats as well as local and global corporations who work together to maintain economic and political domination. Hence, exclusion is no longer solely on the basis of skin colour but economic and political standing is the most significant determinant of social mobility.

Are private schools really private?

Notwithstanding their colonial nature, private schools have remained largely intact even after independence. The only discernible change is their enrolment of elites instead of exclusively white people. Those who defend private schools often argue that they are private institutions and thus not subject to public scrutiny. However, this is not necessarily the case. According to a recent World Bank report on welfare inequality in Zimbabwe, teacher salaries in private schools are government funded. Therefore, the argument that private schools are privately funded cannot stand. The Word Bank report concludes that government funding of private school teachers’ salaries has the effect of worsening inequality. Given this scenario, it seems the majority are subsidising private schools leaving them with excess funds to purchase helicopters and other fancy infrastructure. On the other hand, some students in public schools have to learn in tobacco barns without enough books.

Do the best you can afford?

Another common argument made in support of private schools is that those who can’t afford it must look elsewhere. For some, economic standing must determine the quality of your education. One wonders if such proponents ever heard of Horace Mann’s assertion that ‘education is the great equaliser of the conditions of men’. Take for instance Nicole Hondo’s argument below:

Zimbabweans are crybabies. You spend days crying over Riverton Academy fees of $100k when you have no kids there!Are the parents with kids at Riverton crying? Schools like that are for those who can afford. Iwe do the best YOU can afford. Chero ku States is everyone super rich? pic.twitter.com/A6iMFc6kus

— Nicole Hondo (@nicolehondo) January 14, 2020

Hondo is certainly unaware of the fact that students who receive a poor education suffer lifelong disadvantages in employment, earnings and life expectancy. In Zimbabwe, its mostly those who go to public and missionary schools that suffer this fate. Furthermore, the proposition that economic standing must determine quality of education is highly flawed because it is ahistorical. People do not suddenly find themselves being unable to afford things. Quite the contrary, people’s social conditions determine what they can and cant afford and this is historically determined. For this reason, the public provision of education is of utmost importance not only for social cohesion but to promote democracy. Another significant counter-argument to the ‘do the best you can afford argument’ is that it is based on the failed notion that the state must play a ‘hands-off’ policy approach. Regarding this, private schools argue that theirs is a fight for independent education. And yet, it has been demonstrated that laissez faire policies do not achieve desirable socio-economic outcomes. Instead of showering a minority few with exclusive high quality education, it is much better to combine available resources for the majority to get a decent education.

To conclude, progressive forces must force the government to engage in a radical transformation of the education sector. It is unacceptable that almost 40 years after independence colonial institutions like private schools still exist. A practical way of engaging the government in this debate is to force powerful people to be involved in the conversation. If elites can send their children to exclusive private schools then they are unlikely to be interested in changing the conditions of public schools. Therefore, banning private schools will compel the elite class to seek changes to our education system. Finally, being really educated does not mean being awarded a degree on European concepts. Likewise, there remains significant scope for us to decouple education from the needs of capital in our society. However, this is only possible if we know how bad out existing system is. If you desire to know what it means to be truly educated then watch a 3 minute video by renowned linguist and one of the world’s leading thinkers Noam Chomsky below:

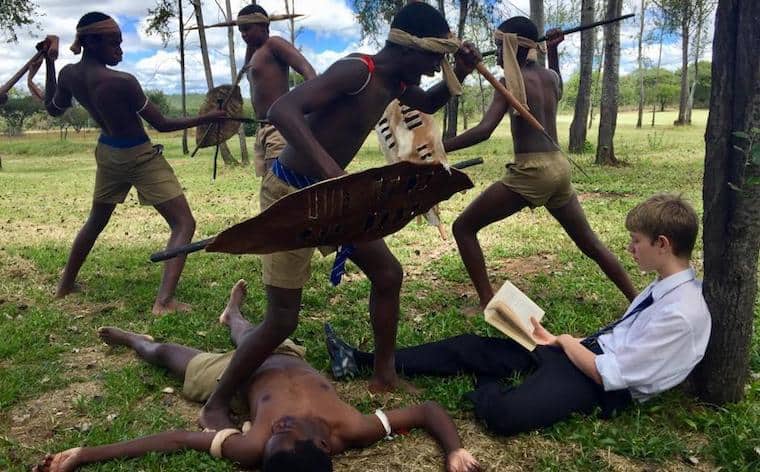

Note on Cover Picture: The picture was posted on social media by Peterhouse College (a private school) in 2019 under a series by the moniker “Extreme Reading Challenge”